Blog

Imaginative TV and the State of Bao

First of all, I must reach out to my beloved Marissa for bringing me an image of the day; her Netflix queue lined up the most perfect mashing to create the best TV show for me in all of existence. Baking is Futile.

Now, onto deeper topics: the state of me, and how I haven’t posted in ages.

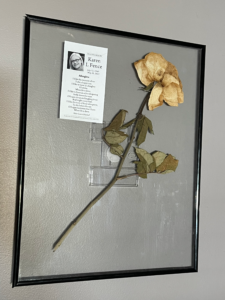

Most importantly: the personal, as it’s distracted me from everything else since January. My father became quite ill and was on hospice for many months, and my mother’s illness finally and rapidly progressed into heart failure. My mother passed in May; my father hung on until August. Both my husband and I were temporary caregivers, and the loss has been felt very deeply. I’m thankful for the friends and family who offered succor during what has been a terrible year for me.

Onward to happier things. “The Eighth Bible of New Egypt” is currently up for serialized purchase via Kindle Vella! Please take a moment to check it out if you haven’t already read it before in anthology form; it’s just in time for Halloween. 🙂 PS — give it a thumbs up! It needs some love on the new platform.

Now, the bigger questions. WHERE’S LENNA? WHERE’S MORE JACOB? WHERE’S THE JANET PROJECT?

Well, those are all really, really great questions and I can answer them all!

Freewoman (scheduled for 2021) is being pushed back to 2022 just because of the sheer insanity of my life these days, but over the next few weeks I should have TEASER ART from my beloved cover artist to tide you all over with.

“Jacob Orange” short stories. I actually have three more coming! One is complete, and two more on the way. There are hijinks with Napa cabbage, Eyeballs (yes, they must be capitalized here), and the divine wrath of Victoria’s high heels. Keep your eyes peeled for a release of the next story, “The Progenitor Machine.”

The Janet Project… I haven’t abandoned you, my beloved retelling of the Scottish ballad “Tam Lin.” I have good news: it’s pretty much done its first round. Then it goes through an edit (or two) from me and some peer review, and fingers crossed, you’ll see it at Barnes & Noble in a couple years. I’m hoping to ship it off to some agents/agencies by year-end, so maybe even earlier than 2023. Ambitious, huh?

I’m going to try to keep the blog up-to-date as time permits. The day job that’s paying the bills is a little intense at the moment, but believe me… there’s more to come!

As a special treat after the break, there’s a writing sample from me for a creative fiction publication. If you’ve stuck around this far, go ahead and read it!

I’m Still Here, Only Barely Undead

2021 has started out as a cracker of a year for many personal reasons upon which I won’t lament, but I would like the world to give us all a break.

In real news, I have two (2!!) new short stories in the works about Jacob Orange, and work on Freewoman is going ahead a little more slowly than I’d like. But I wanted to assure the world amidst all the chaos that I’m still writing. There’s an Amazon promotion for my first novel going on right now, so check it out with your Kindle or other smart devices. Especially my MFA crew!! Here’s a link: Librarian at Amazon.com.

IN OTHER NEWS, I went hatchet-throwing and landed a bullseye. Pim would be proud (those who get the reference, get it; get the book!). Chris and I have been baking LOTS of bread and making kimchi for days.

Monday night will be my first role as dungeon master in about 6 years. I hope I don’t kill all my players (you know who you are…)! There will be lots of kobolds and other nasties to get ’em.

Anyway. It’s just a brief update for now but expect more to come!!

xoxo

“My Curry” and a Happy 70th to my Mom

I love my curries. Thai curries, Japanese curries, Indian curries… but “My Curry” from April Bloomfield is the bestest. I never expected my mother to eat so boldly, but let’s rock and roll, Karen! You’re getting leftovers.

First, some pics:

Look delicious? Here’s the recipe, courtesy of April Bloomfield, with some added touches of my own.

MY CURRY!!

1 tbsp fennel seeds, toasted

2 tbsp cumin seeds, toasted

1 tbsp fenugreek seeds, toasted

10 cloves

2 star anise

3 cardamom pods

3 kaffir lime leaves (or the zest of two limes, if you can’t find kaffir lime leaves)

1 tbsp red pepper flakes

1/2 tsp freshly grated nutmeg

2 tsp turmeric

1/3 cup EVOO

2 cups shallots, thinly sliced

4 cloves garlic, thinly sliced

1/2 small cinnamon stick

1/2 cup finely chopped ginger

3 cups drained and chopped up whole tomatoes (San Marzano is best)

2 tbsp flaky sea salt

8 cilantro roots with 2 inches attached finely chopped

5-inch strip of orange

5-inch strip of lemon

1/4 cup freshly-squeezed orange juice

2 tbsp freshly-squeezed lemon juice

1 tbsp freshly-squeezed lime juice

1 and 1/2 cups pineapple juice

That’s for the curry base. For the meat:

2 tbsp EVOO

4 pounds boneless pork butt (April uses lamb shoulder, but I find it’s harder to get)

2 tbsp flaky sea salt

Method:

Combine everything up to (including) the turmeric in a spice grinder or mortar and pestle until you have a fine powder. Trust me, this is the best curry powder you will have in the world.

Cook the shallots and garlic for ten minutes (stirring frequently) in a Dutch oven until nice and brown. Add the spices, cinnamon, ginger, and cook for 3 minutes. STIR STIR STIR. Add tomatoes and salt and cook, stirring until it’s almost dry — April recommends 15 minutes.

Pour in the juices, peels, and cilantro. Set aside off heat.

Season the pork with salt and brown it in batches with the EVOO. As Anne Burrell says, BROWN FOOD TASTES GOOD. So take your time and don’t crowd the pan.

Transfer to the Dutch oven and cook at 350 F for 1 1/2 hours; then lower the temp to 250 degrees and let it go for another hour or until the pork is fork tender and falling apart. ABSOLUTE YUM.

MY RAITA!

Easy-peasy. One cup of Greek yogurt, one cucumber (diced), and salt to taste.

…and recipe done! Just add rice or some good naan. It looks intimidating, but it’s very easy once you collect the ingredients.

On a separate note, my mother turned seventy today! Happy birthday, Mom! You’re the strongest person I know and gave me a special “Karen Power” that lets me get things done that need to get done.

It’s hard, sometimes, though for me to interact with my siblings. They seem to take no interest in anything I do: be it writing, ballroom dancing, or cookery (though they’re very keen on talking about themselves). All and all it makes me quite sad, but I’m glad my mother had a good day surrounded by those she loves. It makes me happy to see her happy, despite it being somewhat bittersweet.

I once wrote a haiku:

Love stains my shirt / like apple mixed with honey / in the curry you made me.

Another blog post to come soon; this time… not so long! xoxo

Pink Bolognese

So, I dyed my hair pink because… why not? We’re in a pandemic and (1) there’s nowhere to go and (2) if someone says, “Hey, bro! Your hair is pink!” I’m going respond with deuces and quip, “No shite, Sherlock.”

MOVING ON. During the quarantine we wanted something hearty, so we decided on pasta with a bolognese. There’s the traditional method that takes four hours (Anne Burrell, I’m looking at you and still love my Littlepon plushie nested in your cleavage); there’s also Giada’s recipe that only takes a half of an hour. I combined bits from both and made m’own; the next day, I added heavy cream to reconstitute it, and got pink bolognese. Recipe follows!

TO MAKE THE GREAT BAO’S BOLOGNESE:

1 carrot

1 stalk celery

1 onion

2 cloves garlic

1 pound ground beef (I used 80/20, if anybody cares)

1/2 cup tomato paste

1 cup (as much as you drink in a cup…) hearty red wine

1, 28-oz can crushed tomatoes

8 fresh basil leaves, julienned

1/4 cup parsley, chopped

Kosher salt

1/4 cup Pecorino Romano cheese

8 ounces fresh pasta (or dry, but yes, fresh is best)

A good dousing of heavy cream (for tomorrow’s leftovers, and hence the pink)

(1) In a food processor, pulse the carrot, celery, onion, and garlic into a paste. In a pan over medium-high heat, cook the concoction for 15-20 minutes, liberally seasoning with salt. Stir frequently and scrape up the brown bits — as Anne would say, “Brown food tastes good!”

(2) And the ground beef and season (again) liberally with salt. Cook for another 15 minutes, scraping it frequently to work up a fond.

(3) Add the tomato paste and cook for five minutes, stirring frequently until it’s nice and browned. You want the rawness to go away.

(4) DEGLAZE! Pour in the wine and scrape up all the goodness, then let it reduce to almost nothing, about five minutes.

(5) Add the crushed tomatoes, herbs, and a generous amount of salt — they take a lot of it, like a hooker in Atlantic City. Simmer for thirty minutes until the sauce is nice and thick. Add the cheese.

(6) Meanwhile, boil your pasta. I don’t need to tell you how to do that. When it’s al dente, toss it in the sauce. Serve it with more cheese sprinkled on top and a drizzle of olive oil. You’re welcome.

THE NEXT DAY:

Half and half or heavy cream

(1) Reconstitute the pasta in a skillet over medium heat and, once it’s properly hot, add the cream. Cook at a nice simmer until everything looks nice and glossy.

The end.

PS — I’m still in writing mode! Another Jacob Orange story is coming soon!

Breaking the Fourth Wall

Breaking the Fourth Wall:

The Chidings of E. Nesbit in Five Children and It

E. Nesbit was already a successful novelist by the time she turned her hand to crafting works for children. Growing up in numerous towns dotting England and France, she led a relatively happy childhood until ultimately moving back to London. A socialist and partaker in a rocky marriage, Nesbit continued writing children’s books over the course of her lifetime, creating worlds of the fantastic that would inspire authors such C.S. Lewis. She wrote at least 40 novels and collaborated on many more until her death in 1924.

As a writer, I, too, deal primarily deal with the world of the fantastic, where mundane life is peppered with a little magic here and there. Nesbit was the same, taking inspiration from the reality that surrounded her and bringing in snippets of fantasy into her imagined realms. As a child one of my favorite books was Five Children and It, the tale of five young children who discover a Psammead – referred to as a sand-fairy – who, once a day would grant the children a wish. This, of course, becomes the ultimate conflict of the novel: the wishes never go quite as planned, such as when the children ask to be able to fly only to become trapped on a church steeple (all of wishes granted by Psammead ended at sundown).

What I found particularly fascinating about the novel was Nesbit’s propensity to “break the fourth wall,” or rather, have the narrator break narration to make some comment or social remark. While slightly jarring at times, Nesbit becomes something of a forceful Hans Christian Anderson – her work has moral lessons and some questionable asides – but rather than let the narrative always convey that moral, Nesbit at times might just tell the reader what to think:

This is why so many children who live in towns are so extremely naughty. They do not know what is the matter with them, and no more do their fathers and mothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, tutors, governesses, and nurses; but I know. And so do you now.

It is moments such as those that show a shift in narrative voice, one from that of the passive observer to authoritarian. Nesbit is at once informing us of the order of the world, but directly doing so by addressing the reader as though he or she was a child needed scolding. At times, it can be light-hearted information:

“’Humph!’ said the Sand-fairy. (If you read this story aloud, please pronounce ‘humph’ exactly as it is spelt, for that is how he said it).”

There are times, of course, that Nesbit seems to be aware of the extent of her voice. For example, she states “[l]ending ears was common in Roman times, as we learn from Shakespeare; but I fear I am becoming far too instructive.” This style of breaking the fourth wall has been mimicked by authors such Lewis, Carroll, and others.

This style and acknowledgement of occurrences of a magical nature by the other lends itself to creating a liminal space for the reader between the story and the storyteller. Nesbit embraces the concept of the uncanny, a type of fantasy described by Tzvetan Todorov in his classification of the genre. The uncanny, in this instance, is in the moments in which Nesbit breaks the fourth wall and confronts her readers; when readers realize there are magical explanations for the goings-on of the five children, and accept that the mechanics by which the world operates – fairy magic is real – [the work] becomes the opposite classification of the genre, known as the marvelous.

Is this style successful in Five Children and It, or does it break immersion for the reader and take away from the work? For me, it is a question of “telling” versus “showing;” Nesbit at times reveals perhaps too much information rather than give the reader an image with which to work:

I shall not tell you whether anyone cried, nor, if so, how many cried, nor who cried. You will be better employed in making up your minds what you would have done if you had been in their place.

On a personal level, this style did in fact put me off at times. One could certainly read these quips as a series of mere cheeky asides, but there were moments when I felt as though the book should have been titled Five Children, One Adult, and It. I wonder if her tone would remain the same had book been written not in 1902 but in 2018.

Ultimately, Five Children and It is playful romp that delivers a lively – albeit with a slightly forgettable cast of characters – story and, with the help Nesbit herself, some critique of her time period as well. Lines such as “You can always make girls believe things much easier than boys” give the reader a glimpse into what Nesbit’s society believed. I doubt strongly a sentence such as the previous quotation would make the cut for the contemporary children’s novel. These lines distract from the wonder and consequences of the children’s wishes: they are an interruption into a fairly simple narrative that could do without a chiding from its creator.

Still, E. Nesbit remains to this day a beloved author, cherished for her fantastical worlds; I appreciate her contribution to the field of children’s literature. She possessed the ability to straddle both the marvelous and uncanny as described by Todorov, even if her direct addressing of facts to the reader could sometimes detract from greater narrative. As a writer, I find myself avoiding this style, but nonetheless respect the story she was able to create in Five Children and It.

Poetry Review: I hope this reaches her in time

I hope this reaches her in time:

Truncation for Effect

r.h. Sin’s collection of poetry, I hope this reaches her in time, is the journey of a broken heart, of grief, and of rebuilding one’s self. Its poems are terse and to the point, charged with an almost typical angst and “you’ll be okay” sentiment. However, its staccato pacing ties the narrative together through Sin’s truncation of sentences: there are brief spurts of emotion and pared fragments that – albeit briskly – make the collection cohesive.

While not uncommon, this short, fast-punch style suits the arcs of the narrative: being left by a loved one, grieving, anger, and moving on to self-confidence are all emotions delivered with a flow of consciousness voice. The opening poem “good women are tired of giving” sets the tone with a brevity that permeates each piece in the work, cutting through it with short verses such as “the girl who deserves the sun / is tired of being rained on.”

Much like Sin’s book a beautiful composition of broken, I hope this reaches her in time relies heavily on these truncated sentences to produce dramatic juxtapositions: often existing as fragments of sentences, the individual lines punctuate the narrative. These snippets serve as tiny dagger pricks that help convey the poignancy of emotion of the narrator: “aren’t you tired of this shit / the constant struggle / the feeling of loneliness.”

The majority of the poems in the collection, also, evade the usage of proper punctuation full stops, leaving each line on the page hovering in its own space without a sense of stopping. The lack of punctuation permits the reader to string these snippets together, even when they might not necessarily scan as a joint phrase and render a more complex meaning, creating a Joycean effect that reflects the narrator’s state of mind: “and so the loneliness / will grow from the emptiness / you feel / those nights will be the toughest / those mornings, even tougher / it’ll hurt, you should have loved her.”

One key technique throughout the poems seems to lie in the composition of the stanzas themselves; many of the poems start and end with lines that could be taken together, paired on their own. One could cut out the middle lines and glean the entirety of the individual poem. Take, for example, this eleven-line stanza:

and all of this for a love

that turned out to be hatred

all of this for a heart

that never deserved yours

all of this hurt

for a relationship

that would never work

all of yourself

all of everything

invested into something

that now feels like nothing

The efficaciousness of this poem lies in its repetitive nature [of fragmented thoughts], but is ultimately completed by combining the first and last line of the verse: “and all of this for a love / that now feels like nothing.” This technique is employed throughout the work as another form of truncation; the two opening and closing lines package up the meaning in a brief scanning of the poem. While there is some variation to this affectation – obviously notable in the shorter verses – this technique remains consistent throughout and produces a unique, curt effect that propels the narrative forward at a swift, almost frantic, pace: “we become content / deepening the bruises” and “i needed to find myself / while trying to keep you” are two such examples of the proactive nature of the narrator demonstrated through this curtailing of the verse.

Ultimately, the truncation of the lines in I hope this reaches her in time creates a staccato pace throughout the work. It successfully builds up momentum to express the spiraling emotions of the narrator up until the final poem, which is the most truncated of all: “until next time, talk to you soon… / (call ends…).” This ending creates a sense of the narrator experiencing short bursts of emotions and ties together the clipped speech throughout the work; I hope this reaches her in time becomes, in essence, a one-sided telephone conversation with the one who broke your heart.

Poetry Review

Form and Function in

the princess saves herself in this one

Amanda Lovelace is a local author whose poetry went from online popularity and self-publishing to traditional publication with already three editions of the princess saves herself in this one in print. It is a tale of grief, survival, and healing: empowerment of the self and a reminder to “practice self-care before, during & after reading.” The poetry is straightforward and poignant, with most effect coming not from more common poetic devices but by a manipulation of the text itself to achieve a purpose.

The first striking piece of technique that Lovelace employs is in the juxtaposition of her titles; the majority of the collection titles the poem at the end of the piece, rather than in the beginning. This leads the reader directly into the raw emotion of Lovelace – be the subject abuse, alcoholism, or recovery – without any preparation, so each delivery packs a metaphorical punch. For example, consider the following poem:

when i had

no friends

i reached inside

my beloved books

& sculpted some

out of

12 pt

times new roman

& it was almost good enough

Here, the title “& it was almost good enough” not only befits the nature of the poem, but serves as a final closing line as though the title were a part of the poem itself. This technique is employed copiously throughout the collection and provides a unique take on the structure of poetry. Albeit one, short line, the punctuation of the title as a final line is reminiscent of the final couplet of a sonnet; it serves to both summarize the poem and provide an impactful delivery.

Lovelace also enjoys the shape of her poetry: verses themselves are typographically modified to enhance the theme of individual poems. Although not an unfamiliar technique, the restraint and deftness with which Lovelace employs shaping her words allows for multiple readings of each and furthers the narrative:

the princess woke

to feel her castle rocking

back & forth

back & forth

back & forth

This structure repeats but softly gives a cadence of rocking that gradually increases until the climax of the poem: “at first / she thought / a hurricane / must be brewing, / but she was / wrong.” The wavering nature of the poem ending on the word “wrong” substantiates a sense of imbalance or something amiss in Lovelace’s psyche as she crafts the poem.

Lovelace, at points, goes quite literal in the shaping of her poetry, letting the physicality of a word dominate a poem in a picture:

there

was never

enough alcohol

to keep my mother warm

in a house

as cold as

t h i s.

With this poem, the imagery is overt – as to whether it is too literal is subject to debate – but the poem still manages to backload panache by the stinging expansion of the word “this” in the final line. Due to its spacing, one is drawn immediately to the word. “This,” Lovelace is saying, “This is my point,” referring to the text before it, shaped as a house supported by a weak pillar of gapping between the foundation of the house-structure itself. The spaces, then, represent the cracks in a house ruled by this, the mother’s insatiable desire to keep herself from the “cold” by indulging her alcoholism.

This gapping is further employed in words like “s h a t t e r e d” or the scattering of words in the shape of a spiral: “death / wound / itself / around /her / bones / like / a / piece / of / red / ribbon.” There is a certain calculated playfulness – despite the serious subject matter – in the construction of these poems that harkens back to the title, the princess saves herself in this one. By manipulating the words into the shapes she desires, Lovelace is ultimately taking control of the power of the written word on both a physical and spiritual level.

Form and function in Lovelace’s collection subvert the reader’s expectations of free verse by subverting and reshaping the text itself. The juxtaposition of the title at the end of the verse rather than the beginning places a period and stamp of force on the individual poems, while manipulation of individual letters or words similarly compels the reader to look at the poem from a different perspective. Each piece could certainly stand alone as free verse with no fiddling, but there is a thoughtfulness in the structure of the shape of words that conveys emotion and image with poignancy. In this manner, Lovelace’s poetry successfully transcends the confines of language. To further cap off her fancy, flipping to the back cover of the book one can find the ending line of the series, emblazoned in bold, large font just as the front cover, the alternate title (or perhaps, as many of her other poems, the actual title) of the book itself:

the story of

a princess

turned

damsel

turned queen

It’s that time of year again…

Taxes, taxes, taxes. I know I’ve been MIA for a solid two months or so, but work and family have kept me away from the best part of my life — writing!

The Janet Project is currently still a WIP, but doesn’t have much more to go. Then I get to go through the joy of query letters! *shudder* If anyone has suggestions on a good way to write one, I’m more open than an Atlantic City hooker. Too crass? Too bad. Query letters stink.

As my day-job is in the financial field, I wanted to explain to those who write exclusively as their source of income that you might not have tax withheld from your advances and royalties. If you don’t want to owe a lump sum in April, you should pay estimated tax (April, June, September, January [of the next year]). This is more or less the same concept of withholding, as here in the US we’re required to PRE-PAY our taxes. So, to avoid any penalties… fork over some of your tax liability during the year and don’t get whammied up the rear end in April. 😉

This is perhaps the most boring post I’ve ever written, so I’ll link to a great music video by a group Chris and I are going to see live on Tuesday. It’s Snow Halation, by μ’s. It’ll be a nice diversion from all the stress going on right now. Definitely check out the vid and TODOKETE!! with Honoka.

Bao for Bao 〜バオ作り〜

Happy 2020, everyone! I hope everyone rang in the New Year with something fun and delicious.

Speaking of deliciousness, hubby (who is obsessed with all types of bao, including me — my nickname happens to be Bao-Bao) made David Chang’s pork buns today from scratch. How amazing is that?

And then, of course, we have the final product: a bao with pork, pickled radish and cucumber, hoisin sauce, and a little sriracha for good measure:

What is everyone eating to pick up their spirits? It had better involve wine!

Happy 2020.

xoxo